About this deal

There was a clandestine, quite active sabotage movement — who supported Hitler in South Africa — of extreme right-wing Afrikaner nationalists. Very anti-British and also very racist. That was around. There’d be strange things when you entered a cinema. They always ended with playing, “God Save the King,” and you were expected to stand. Most people would stand, and some would sit. That was their little way of publicly showing their opposition to the war. Albie awakes one morning to find himself the prime suspect in a serious crime. Mr. Kidhater-Cox's car has been stolen, and he demands justice. The issues of conscience played a bigger role in my life than issues of race. I didn’t have to overcome the usual racial stereotypes and prejudices that most white kids had growing up and battle for years afterwards to get rid of those prejudices. I wouldn’t say I wasn’t influenced by them. They seep in all the time consciously and unconsciously. It wasn’t a major battle for me. But the question of integrity of conscience — what it means to you as a human being, as a person, to believe in what you believe, not to pretend to believe because people expect it of you, even people close to you, even people whom you love, or your community or your peers at school, but because you truly believe, because it’s true to you and it’s part of who you are — that I kind of worked out at that age. And as I say, I often felt very, very lonely, very lonely and — but I got through it. A lot of people who were living in exile were vulnerable. Farmers in their fields, people in hospital. Everyone became a target. But I still wasn’t happy. I would sometimes say, “Even when I’m happy in England, I’m unhappy.” I loved London. I’d take people around London. I went to shows, I heard music. I had really good friends there. I loved teaching at Southampton University. I discovered modern dance, contemporary dance, so many things, but there was a deep sadness inside me. And I remember when we used to have ANC meetings, they’d always be in drafty little halls with broken windows. I’d often be wearing a heavy overcoat and there would be nice soft seats. They would be old-fashioned halls that you didn’t have to pay very much for. And you’d get up, and the seats would all clatter, clatter, clatter. And we’d sing “ Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” and people would raise their right arms with a clenched fist salute. And I couldn’t raise my right arm. It wasn’t a decision on my part. I just didn’t have the courage, I didn’t feel that strength. And I’d be the only one in a room with maybe 20 people, maybe 50, maybe 10, without giving the salute of the organization. And then I went to Mozambique in 1976. I’d been teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam during one of those long English summers. You finish marking your exams, and I was able to teach a whole term in Dar es Salaam without missing a day of work at the Southampton University, and have a week left over, during which I went to newly independent Mozambique.

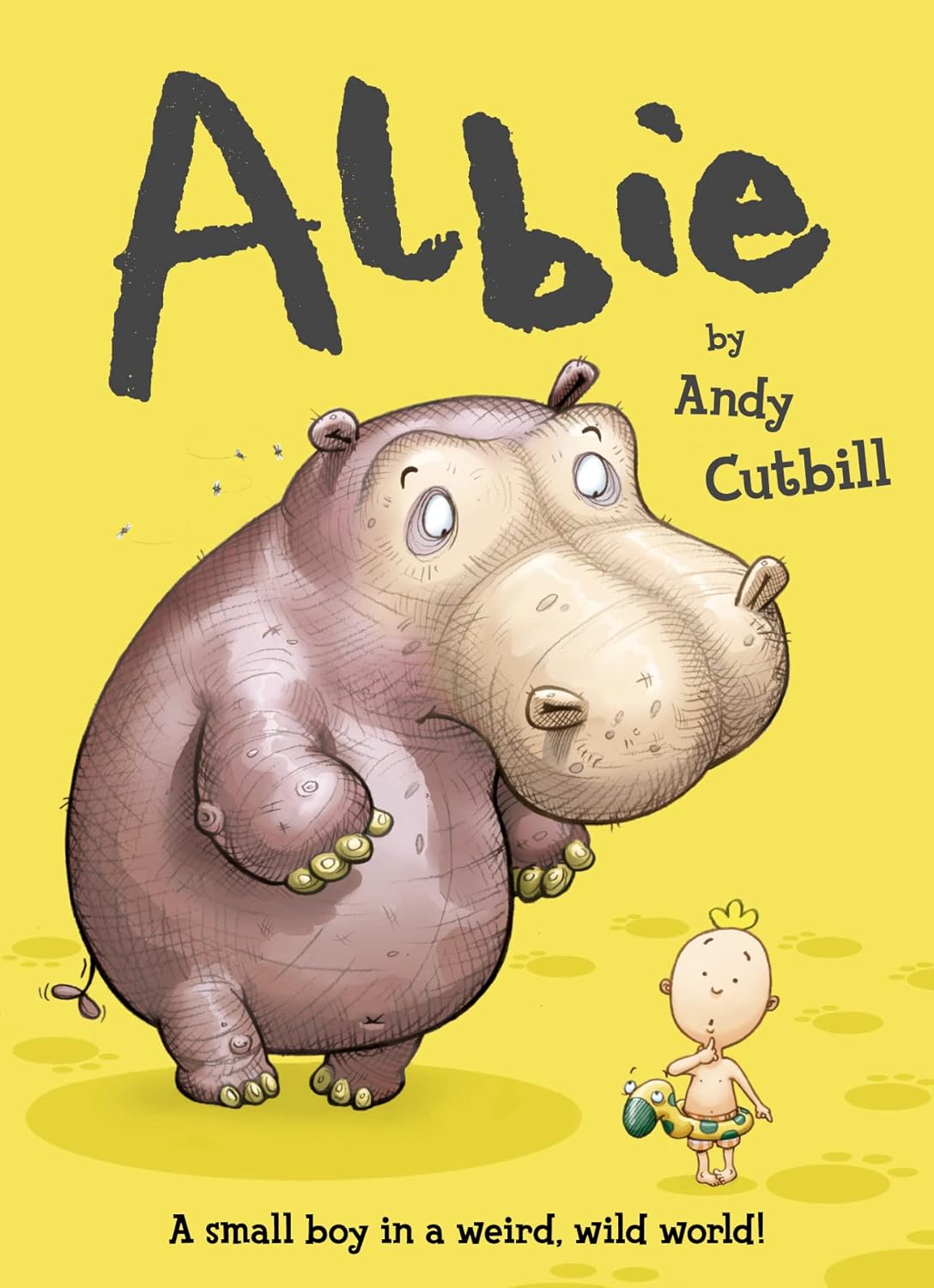

This anniversary definitely called for a celebration so we were asked to be part of a special blog tour about ten years of Albie, with each stop starring a different book and the chance to win a copy! Albie Sachs graduated from secondary school at 15, and entered the University of Cape Town, where he soon fell in with a group of like-minded students known as the Modern Youth Society, dedicated to free thought, progressive politics and an egalitarian, multiracial society. In 1952, at age 17, he joined a campaign of civil disobedience against apartheid, the Defiance of Unjust Laws Campaign. He was arrested for sitting in an area of the General Post Office reserved for non-whites. He was released when the judge learned his age, but it would not be his last run-in with the law. 21-year-old attorney Albie Sachs stands up for freedom. The Congress of the People meets at Kliptown in 1955 to adopt the Freedom Charter, calling for a mulitracial democracy in South Africa. (Robben Island Museum Archives) Most of the planets we know about would not make great homes for humans. They are too hot, too cold or have no air to breathe. Because most planets are very VERY far away, it’s hard to find out whether there are any other kinds of living creatures there.

Space Oddity

I had a book, The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs, my first book, which was converted into a play and put on by the Royal Shakespeare Company and broadcast by the BBC. I even went to the play one day. There was an American tourist sitting next to me, and I was dying to nudge him and say, “You know what?” And some stupid sense of dignity made me feel, you know, that’s a bit cheap, and I’m sorry now, it would have been a nice story for him. And it was marvelous the way they spoke. I mean the actors, British actors, were tremendous. And when I was sitting in jail I used to imagine a play by me being put on at a theater in England. Somehow applause from an English audience in theater, that was the highest applause in the world you can get for anything. And here I’m actually sitting in the theater and people are applauding, not me but the play. Did you come to know Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission? When did you first meet Archbishop Tutu? Months passed, and I’m at a party at the end of the year, and the band is playing. I’m very tired. We work very hard as judges. I hear a voice says, “Albie!” I looked around. “Albie!” My God, it’s Henri! And we get into a corner and I say, “What happened? What happened?” And he said, “I went to the Truth Commission, and I spoke to Bobby and Sue and Farouk.” He’s calling me Albie. He’s using their first name terms, people who were put into exile with me, who also could have been victims of the bomb. “I told them everything and you said that one day….” and I said, “Henri, only your face tells me that what you’re saying is the truth.” And I put out my hand and I shook his hand. He went away absolutely beaming, and I almost fainted. I heard afterwards that he suddenly broke away from that party. It was television people. He went home and he cried for two weeks. That moved me a lot. To me that was more important than sending him to jail. I wrote a book called The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, saying that if we got democracy in South Africa, roses and lilies would grow out of my arm. Sending people to jail wouldn’t help me at all, but to get the country we’d been fighting for, that would be quite wonderful. That would be my soft vengeance. And now Henri and I — I don’t phone him up and say, “Let’s go to a movie.” But if I’m sitting in a bus and he sits down next to me, I say, “Oh Henri, how are you getting on?” We’re living in the same country because of the Truth Commission. The earliest mention of aliens was by a writer called Lucian of Samosata around 1,800 years ago. He made up a story about travelling to the moon and discovering all sorts of life there including vultures, and birds made from grass! I wanted to be a freedom fighter, doing something special for my life, for my country, and what this did was make me the equal in a marvelous — and in some ways a terrifying way, of the oppressors, of the rich, of the poor, people who’d done nothing. It was like a very ordinary act, and it’s not easy to become ordinary. Then I would start telling myself, the paradox of South Africa was we’d fought — all our passion — to create a boring society. A boring society in the sense that people didn’t kill each other and push each other around. We had all the normal complaints and dramas and hopes and disappointments of a democratic society.

Occasionally at school we would have memorial services for a kid whose dad was killed in the war, and there’d be a kind of a gloom and we would sing, “Abide with me, fast was the eventide.” It still resonates in my head. It’s six decades or more later, but it was done in that funereal way. It wasn’t real, it wasn’t tears for someone close, it was kind of institutionalized, but it was part and parcel. Perhaps the tough part was preparing young boys to kill and to be killed, to be soldiers. It wasn’t an accident I read that, because there were many refugees from Germany whom my mother was very friendly with. And we even got her into trouble, because my brother and I went around very primly, aged about four and three, or five and four, telling the other kids, “You mustn’t say all the Germans are bad. You mustn’t say the Germans are bad. It’s the Nazis who are bad.” Again, you know, quite tough for a little four-year-old and yet, that was also combating stereotypes. You were in an all-boys school with a cadet program. Marching and rifle practice, and so on. What was that like for you? Reg and Spike find a piece of paper with directions on it, and immediately decide that it's a treasure map.David Edgar did a most marvelous adaptation, and I did quite a lot of broadcasting and I wrote. My Ph.D. was converted into a book called Justice in South Africa, and it won some prizes and was well received. And then years later, I wrote a book called Sexism and the Law. It was the first book on the way the legal system, as a system, had kept women out, denied them the right to practice as lawyers. The way the judges had used the word “person” to say, “a person means a male person,” so that they’d even distorted the English language to keep women from voting, from practicing as barristers, from doing a whole range of things that men could just do. That was my contribution to British intellectual life. And it was published in America, California University Press, but they wanted an American counterpart and I met, through that, Joan Hoff Wilson, and she did the second part of the book. We hadn’t even met and I said, “Dear Joan, you don’t know me. Your name was given to me by somebody you don’t know either, but this is my manuscript. Can you do the American part?” She wasn’t a lawyer, she was a legal historian and she did the most marvelous section. So this was the first book in the world I think on sexism and the law. And I’m happy to say that many other books have followed and I’m sure improved on it. What was bad was we didn’t meet with girls as friends, as equals, as people sharing tasks, and dating became very difficult. It was very problematic for me. I was very, very awkward. We would have an annual school dance at the end of our last year. The girls’ school had a dance, and I was invited to be a kind of a blind date for someone. And I had a certain courage. I actually asked the headmistress to dance. I couldn’t put one foot in front of the other, but I wasn’t afraid. I quite enjoyed going and I enjoyed spending the evening with my partner. But I felt very raw inside. I put on something of a front. And then I wasn’t safe from all that until I joined a youth group at university. That was terrific. They had boys and girls, we were equal. The girls were — the word “feminist” wasn’t being used at the time, but they were very independent. It wasn’t couples: boy, girl, boy, girl, girl, boy. Albie Sachs: That’s a boring question. An interesting question is what’s a guy like me doing, being a judge and becoming a judge. But I was born in the Florence Nightingale Hospital in Johannesburg, which happens to be directly across the way from where the new Constitutional Court has been built, in the heart of the Old Fort Prison.

Albie Sachs: I was how old? I was born in 1935, so now we’re 1939, so I was four and a bit. It was everywhere, on the news, people were speaking about it. I can’t say I remember where I exactly was when the first radio broadcast came of the Nazi invasion of Poland. It dominated by childhood. War, war, war. We read about it, we heard about it. It was far away. It was a big abstraction out there, the terrible enemy. I had some uncles who joined the army, and in South Africa they called it “going up north.” You went from South Africa to fight up north. I think everybody wonders, “If I were to die tomorrow, would anybody cry?” And people thought I was dead, and they cried, and I knew that. I never have to ask that question again. It’s not a real question you ask, but it’s something that’s inside of you that you wonder about. And so much love came, and I developed a connection with England that I’d never had before. I’d lived there. I’d worked there. I’d written books. My children were born there, grew up there, but now it was the nurses taking off the bandages, cleaning my body, washing me with love and tenderness and… organized. It made me appreciate British people with an affection and a closeness far deeper than anything that I’d had before, and I emerged from that, I think, a warmer and more generous and a better person, and ready for the tasks at hand in South Africa. Albie wakes in the night to go to the bathroom. But when he gets there, he finds that the bathroom fixtures have been removed. Albie's morning viewing is interrupted by a newsflash: a violent lunatic is on the loose... and according to the picture, it's Vulgar Olga!I also love how relaxed and happy Albie is with his new friend and how excited he is to be creating his own story in the wall of her cave! While preparing a sandwich in the kitchen one morning, Albie discovers a hungry elephant in the cupboard. The one is, to me, the question of conscience is number one. It comes before food. You can survive on almost anything, but your dignity depends on your conscience. And if you’ve got the right conscience, and you meet other people with the right conscience, you get together. You solve the problems of food, but you can’t solve the problems of conscience just through food, and through eating and dining and wining and whatever. The other thing is it’s made me enormously respectful of the beliefs of others. It was so difficult to be a non-believer in a believing, or sometimes pretense-believing environment. It’s made me hugely respectful of belief, of religious belief of all religions, of all faiths. And strangely enough, when years later, Oliver Tambo, who was the President of the ANC, wanted somebody to help him prepare for a meeting of world leaders of conscience and religion, he didn’t go to the religious desk of the ANC to discuss it. He came to me. He came to me, and we worked on themes together. He just felt there was something deeply respectful of conscience and belief, not sectarian. The religious desk of the ANC would say, “How can we get the Catholics on our side? What can we do for the Muslims, for the Jews?” and so on. And that wasn’t what it was about. It was about that intrinsic respect for human dignity, for conscience, for belief of all people that Oliver Tambo — this very, very committed Christian who often thought of giving up politics to become a full-time minister in the Anglican church — and Albie Sachs, who had grown up in this totally secular home — we just got on. Got on like that because, I think, of our mutual respect for conscience.

Great Deal

Great Deal